Why the Eye Almost Broke Darwin’s Theory

A deep-time account of how life first learned to see

Charles Darwin was confident and meticulous. He had spent decades cataloguing the natural world and shaping the idea that would redefine biology: evolution by natural selection. Yet there was one structure that refused to make sense. The eye, with its magnificently precise engineering, seemed too perfect to arise through small, random steps. Darwin devoted an entire chapter to the problem of the eye. Fortunately for us, he also left clues to its solution. This article begins at Darwin’s moment of hesitation and follows the improbable journey of how life first learned to see.

What troubled Darwin was not simply that the eye was complex, but that all its parts worked together so precisely. It was difficult to imagine intermediate stages that could also be functional. In his words:

“To suppose that the eye, with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible degree.”

Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (1859).

Darwin was not alone. Decades later, the same scientist who managed to unravel how the brain communicates and established the neuron doctrine that overturned the belief at the time, also found himself stopped by the eye. Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the father of neuroscience, admitted that no structure challenged him more:

“In the study of [the retina] I for the first time felt my faith in Darwinism (hypothesis of natural selection) weakened, being amazed and confounded by the supreme constructive ingenuity revealed not only in the retina … but even in the meanest insect eye. I felt more profoundly than in any other subject of study the shuddering sensation of the unfathomable mystery of life.”

Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Recollections of My Life (1898), p. 576

Ask anyone. The more you know about the eye, the closer it feels to magic than chance.

We now know vastly more than Darwin and Ramón y Cajal could have imagined, and it remains equally breathtaking. To put this complexity in perspective: while the human heart has a sophisticated network of roughly 60 cell subtypes, the eye relies on nearly 160, with over 120 specialised types packed into the retina alone. This dense biological machinery allows your eyes to see objects kilometres away and read words centimetres from your face, detect rapid movement in the periphery, and operate across a brightness range spanning nearly a billion-fold, from starlight to sunlight. Not for nothing, vision is the only sense with its own dedicated brain lobe.

If you are still not impressed, you can read here about how cones and rods work to give you maximum flexibility and incredible precision..

But Darwin did not stop there, he pointed a way forward:

“Yet reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a perfect and complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its possessor, can be shown to exist; if further, the eye does vary ever so slightly, and the variations be inherited, which is certainly the case; and if any variation or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, can hardly be considered real.”

Darwin (1859).

Let us unpack that.

He does not deny that the eye could evolve. He accepts an imperfect eye, but insists that each successive improvement must give the organism an advantage great enough to be passed on.

The task becomes easier if we flip the question and ask what an organism can do with a slightly better eye. Each new small improvement gives the animal an opportunity to do something new in its environment. Dan-Eric Nilsson (2013) argues that if an innovation in eye development leads to a behaviour change, then the evolution of the eye is really the evolution of visually guided behaviour. Let us explore what this means with a story. Come a little closer.

The evolution of visually guided behaviours.

Let’s imagine a very simple organism. Let’s call him Jonas.

(I)

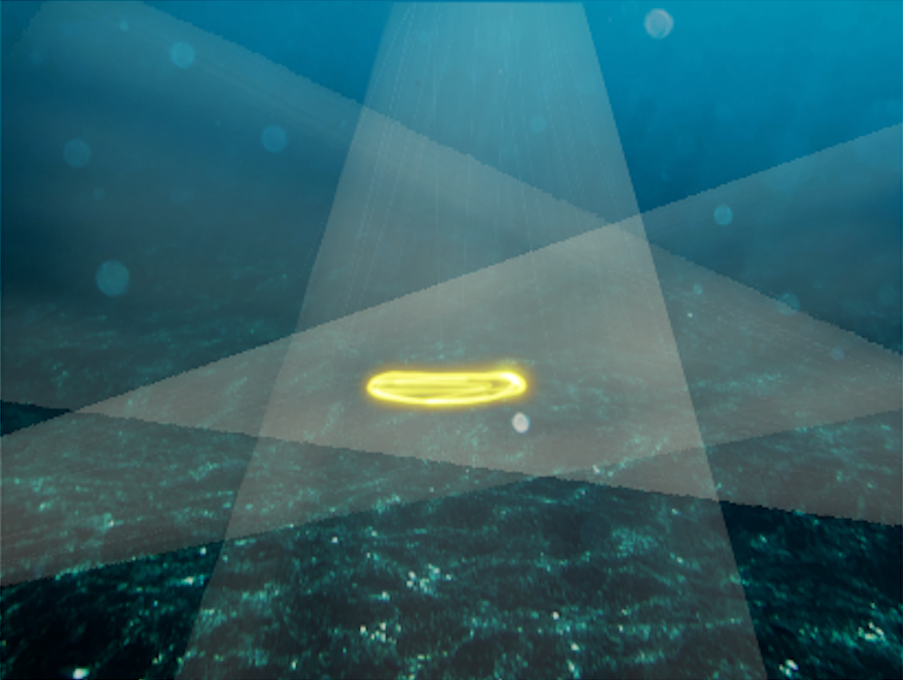

Jonas lives in the sea, long before complex animals appeared. He is a soft, flat-bodied organism, little more than a sheet of cells drifting about. He does not have eyes, but he just gained a single light-sensitive cell that converts light into an electrical signal. This may not sound impressive to you, but for Jonas, this is the difference between night and day. Literally. Jonas can now notice when there is daylight and regulate his circadian rhythm. Not only this, but as a marine animal, this light sensitivity gives Jonas some information about depth, because light is rapidly absorbed and scattered by water. Darker means deeper.

This is not vision as we know it. Jonas can only detect very slow changes in ambient light.

(II)

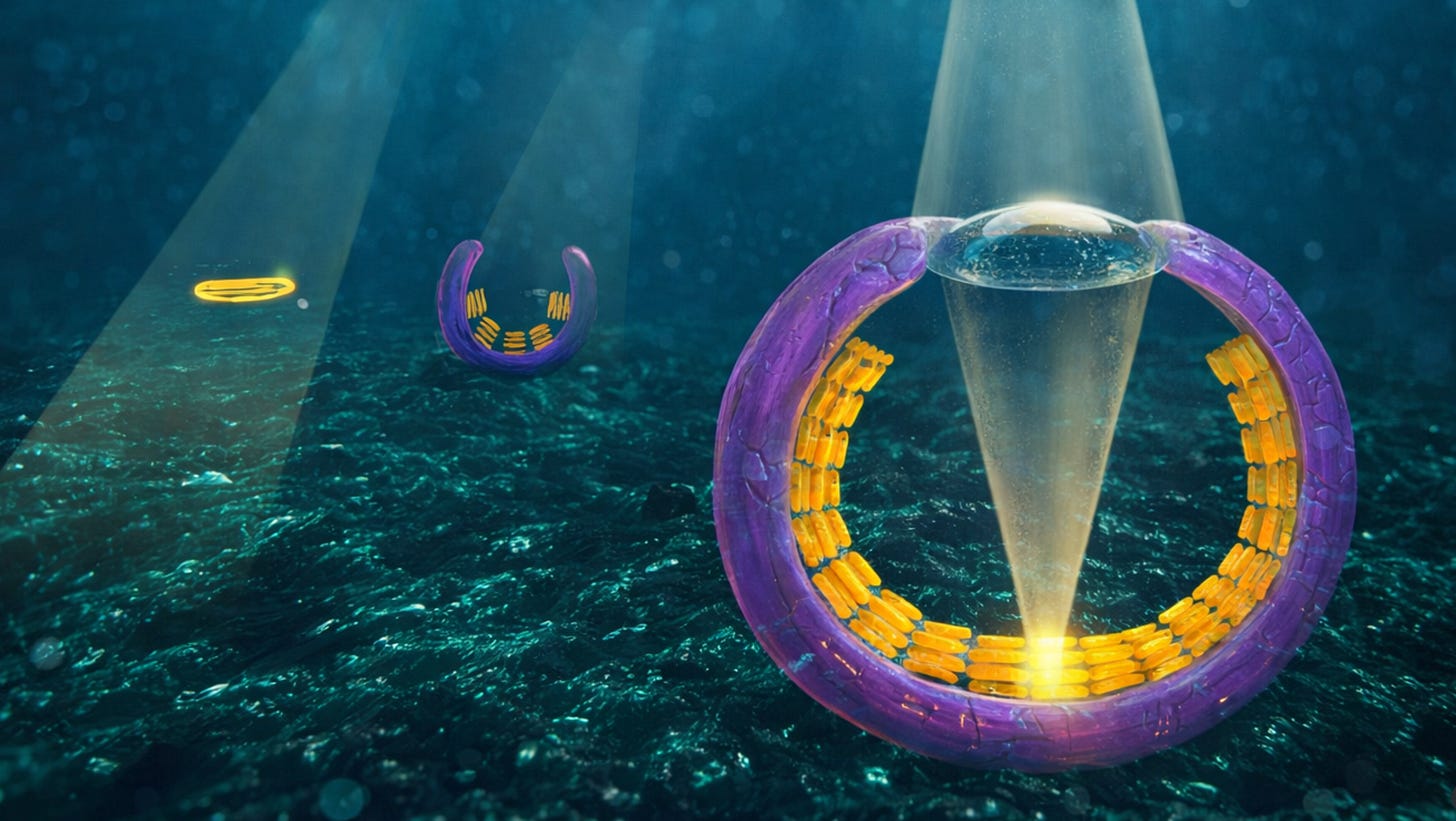

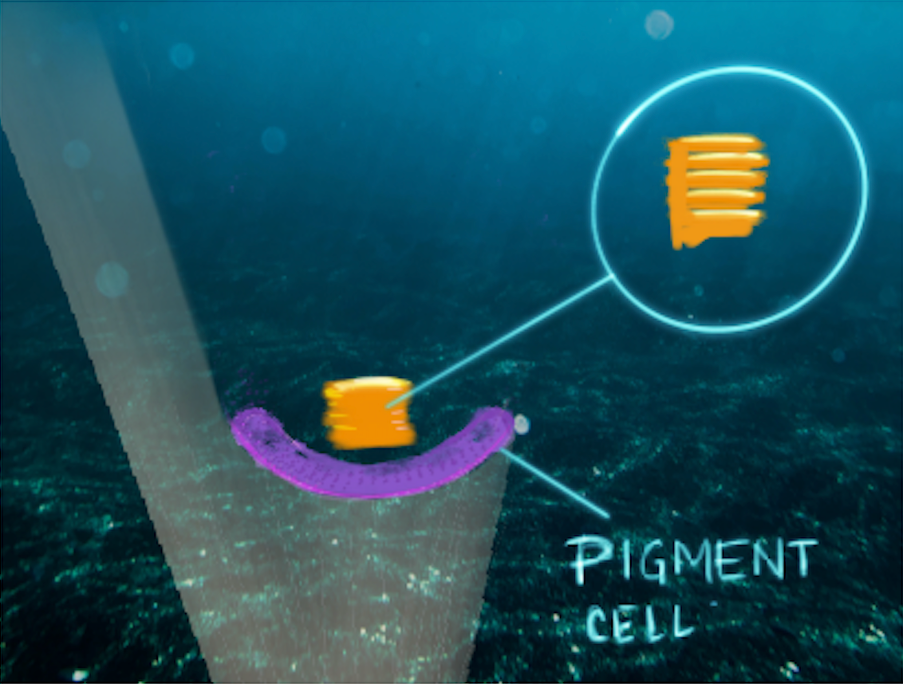

Millions of years have passed, and, among other innovations, Jonas has gained a pigment cell. This cell acts as a screen, absorbing light and shielding one side of the light-sensitive cell.

Light can now reach Jonas only from the unshielded side, which means that now he can tell where the light is coming from. Yet, direction becomes meaningful to Jonas only if he has the ability to move. And he does. With this new trick, he can move towards or away from light, a behaviour called phototaxis. He can also orient himself, because he now knows where he is in relation to the light.

Around the same time, inside the light-sensitive cell itself, another subtle change is taking place. The light-sensitive membrane begins to fold inward, creating folds that increase the surface area exposed to light. More membrane means greater sensitivity. This simple structural change dramatically boosts sensitivity without changing the cell’s overall size.

(III)

Some more millions of years have passed and Jonas has many more photoreceptors, and his once flat eye has folded inward, forming a shallow cup. This changes everything. Light entering the cup now strikes different receptors depending on its direction, allowing Jonas to form a crude spatial pattern.

Jonas can now, for the first time, form an image.

Life looks extremely blurry, more like shifting patches of light and dark, but even this coarse spatial pattern allows him to steer more accurately, avoid obstacles, and navigate through his environment with intention rather than drift.

As the cup deepens and the opening narrows further, direction becomes more precise. A shadow moving across his eyes could mean a predator, so now Jonas can see the danger and escape.

(IV)

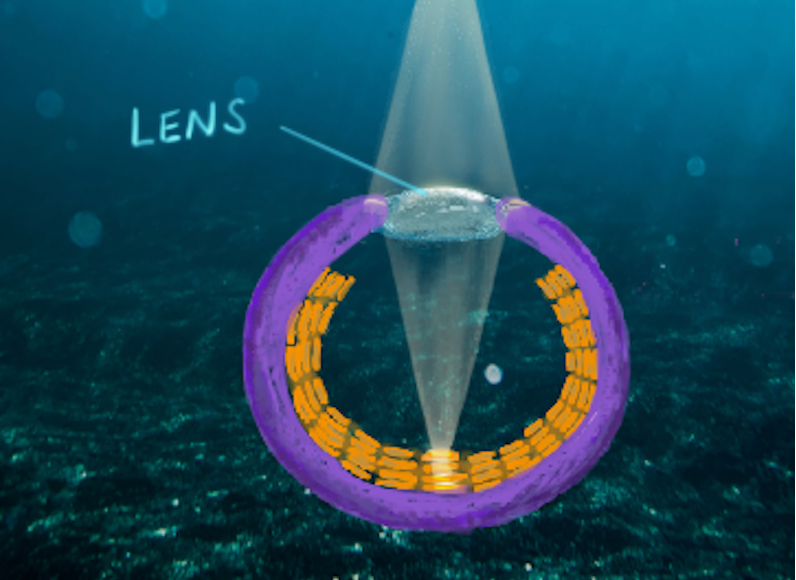

Some millions of years later, Jonas’ eyes have continued to refine. As the cup deepens, it becomes easier to determine the direction of incoming light. Yet, the most important change is the gradual appearance of a lens.

This may have begun as a transparent layer serving a protective role against debris or harmful UV light, but over time it became a powerful optical innovation. By bending incoming light, the lens concentrates rays onto a smaller region of the retina, now densely packed with photoreceptors. This dramatically increases contrast and sharpness.

This refinement transforms vision and comes with a bigger eye to accommodate the optics. Jonas can now resolve finer details, distinguish objects from their background, and judge distance with greater accuracy. This means he can not only avoid predators but actively hunt, tracking prey, planning movement and interacting visually with other animals. Vision becomes a powerful guide for behaviour and interaction.

Other Ways of Seeing

Jonas has come a long way, and you have seen only snapshots in an endless sequence of small advances. But this story follows only one evolutionary route: the one that leads to a single-chamber, camera-type eye, the path taken by humans, frogs, and leopards. Jonas got an eye built for fine detail.

Other lineages branched off at different times and produced eye structures best suited to their own environmental challenges. You can learn more about how here.

Jonas’ cousin Marina did not develop a single chamber. Instead, the surface of her eye formed multiple shallow folds, each with its own lens and its own sampling direction. This gave Marina a dramatically wider field of view than Jonas had, an eye built for vigilance rather than detail, ideal for spotting predators approaching from any direction. Flies have this type of eye. Have you ever tried catching a fly with your hand?

From zero to eye in 170,000,000 years flat

What Jonas experienced as a story corresponds to a well-supported evolutionary sequence. Dan-Eric Nilsson describes eye evolution as progressing through four main stages of structural and behavioural innovation:

Class I - Non-directional light-sensing → regulation of circadian rhythm

Class II - Directional light-seeing → phototaxis and orientation

Class III - Low-resolution vision → navigation, obstacle avoidance

Class IV - High-resolution vision → active predation, visual communication

Nilsson and Pelger (1994) estimate that the transition from a simple light-sensitive patch to a fully developed camera-type eye could have taken as little as 170 million years, and that this process was likely completed by the early Cambrian (~530 million years ago). Using conservative assumptions, the researchers calculate that fewer than 400,000 generations would have been sufficient.

This means that once light sensitivity existed, eye evolution developed fast, propelled by immediate behavioural gains under constant environmental pressure.

Hard evidence

Fossil records support Nilsson’s rapid timeline. By the early Cambrian, around 515 million years ago, animals already possessed anatomically sophisticated eyes. These are two examples of arthropods, the evolutionary ancestors of insects, spiders, and crustaceans:

Anomalocaris: a large predatory animal, up to a metre in length, and likely the dominant hunter of its time, with large eyes mounted on flexible stalks that projected from the head. These would be compound eyes (like Marina’s eyes) with thousands of tiny lenses arranged in a hexagonal grid, possibly as many as 16,700 lenses per eye (Paterson et al., 2011).

Microdictyon sinicum: an animal resembling a worm with legs, representing a transitional step between soft-bodied worms and the jointed, armoured arthropods. Fossils show lens-like structures on each body segment, suggesting that early eyes could have been distributed in the body instead of being in the head.

Could vision have accelerated evolution?

The Cambrian explosion was a brief period of about 20-25 million years (540 - 515 million years ago). During this time, animal life changed rapidly from small soft-bodied organisms to large, interacting animals with specialised tissues and hard parts, like shells and exoskeletons, which could fossilise. We are still talking about marine life only, no terrestrial ecosystems yet.

The timeline for eye development suggests something counterintuitive: complex, high-quality vision appears around the beginning of this evolutionary burst, not as a late refinement.

In this context, researchers argue that vision could have intensified evolutionary pressure. Better eyes raised the stakes on both sides: seeing predators and prey at a distance favoured the evolution of speed, armour, camouflage, and ever faster and more specialised perception.

Where Jonas lives on today: modern animals

Evolution does not move towards complexity for its own sake. If a sensory system fits the brief of what the animal needs and the environment does not demand any more, there is no pressure to change. For this reason, many animals alive today still rely on visual systems similar to the stages we followed with Jonas, not because evolution stalled, but because these designs remain excellent solutions.

Class I – Non-directional light sensing

Some simple marine animals like corals and sea anemones use light sensitivity to track day-night cycles.

Class II – Directional light sensing

Flatworms are soft-bodied and vulnerable to desiccation and UV damage. A simple photoreceptor paired with a pigment cell gives them enough directional information to find shelter under rocks.

Class III – Low-resolution vision

The nautilus and some molluscs have cup-shaped eyes without a lens. These form low-resolution images sufficient for detecting shape and movement, supporting navigation and basic obstacle avoidance.

Class IV – High-resolution vision

It is hard to choose an example because there is a great variety of eye systems that are familiar to us. Three major groups belong here: vertebrates, cephalopods and arthropods. These animals have lenses, sometimes multiple ones, and the ability to form sharp, detailed images. Some use this sharp vision to hunt prey, while others use it to order food online.

If this raised questions rather than answers, that is precisely what this is about. Feel free to share what you are still wondering about below.

All together now…

Function drives evolution. Eyes did not evolve because complexity is inherently “better”, but because each small improvement enabled a new behavioural advantage, exactly as Darwin said, and those advantages compounded over time.

Vision changed the rules. Once organisms could sense the direction of light and form even crude images, natural selection intensified. Predator and prey were no longer reacting on contact but at a distance, reshaping how animals moved, hid, hunted, and survived.

Darwin was right to hesitate. Even today, with genetics, high-resolution imaging and computational models, the eye remains one of the most astonishing systems evolution has produced. Explaining how it evolved does not drain it of its wonder. If anything, the deeper we look, the more unfathomable the eye becomes.

And so, it feels fitting to end where Darwin himself paused:

“How a nerve comes to be sensitive to light

hardly concerns us more than how life itself first originated.”

Darwin (1859).

Coming next…

So far, we have spoken about multicellular animals and how light sensitivity was rapidly refined into vision. But light sensing did not begin with animals, it began billions of years earlier.

Join me in Part 2 as we go back to where life first sensed light.

It takes a lot of work and time to write these articles. If you find value in what you just read and want to support my work, you can buy me a coffee.

In any case, if you got this far, please like and restack, and feel free to drop any questions in the comments.

REFERENCES:

Cajal, S. R. Y. (1989). Recollections of my life (Vol. 8). MIT press.

Darwin, C. (1964). On the origin of species: A facsimile of the first edition. Harvard University Press.

Nilsson, D. E. (2013). Eye evolution and its functional basis. Visual neuroscience, 30(1-2), 5-20.

Nilsson, D. E., & Pelger, S. (1994). A pessimistic estimate of the time required for an eye to evolve. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 256(1345), 53-58.

Paterson, J. R., García-Bellido, D. C., Lee, M. S., Brock, G. A., Jago, J. B., & Edgecombe, G. D. (2011). Acute vision in the giant Cambrian predator Anomalocaris and the origin of compound eyes. Nature, 480(7376), 237-240.