The Unlikely Origins of Seeing

Tracing vision back to its beginnings, and the genetic accident that enabled it.

Have you ever wondered why vision is so common across living things? Why is vision so important that most animals developed it? Eyes are everywhere and in so many radically different designs that it is hard to think they evolved from one another.

Even Darwin found the complexity of eyes difficult to explain.

To suppose that the eye, with all its inimitable contrivances … could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible degree. Darwin (1859)

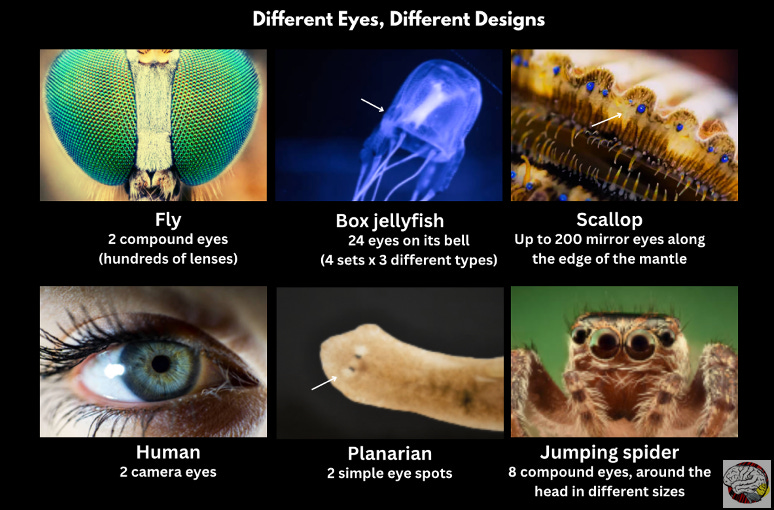

There are vast differences between the eyes of insects, mammals, molluscs, birds and others. Not only do they have entirely different eye structures, but are also differences in the numbers and placement of eyes (not always on the head). Some animals have functioning eyes that produce no images at all. It is hard to think that all eyes evolved from an earlier version.

Why would evolution invent eyes again and again? What does that tell us about the fundamental importance of vision for survival?

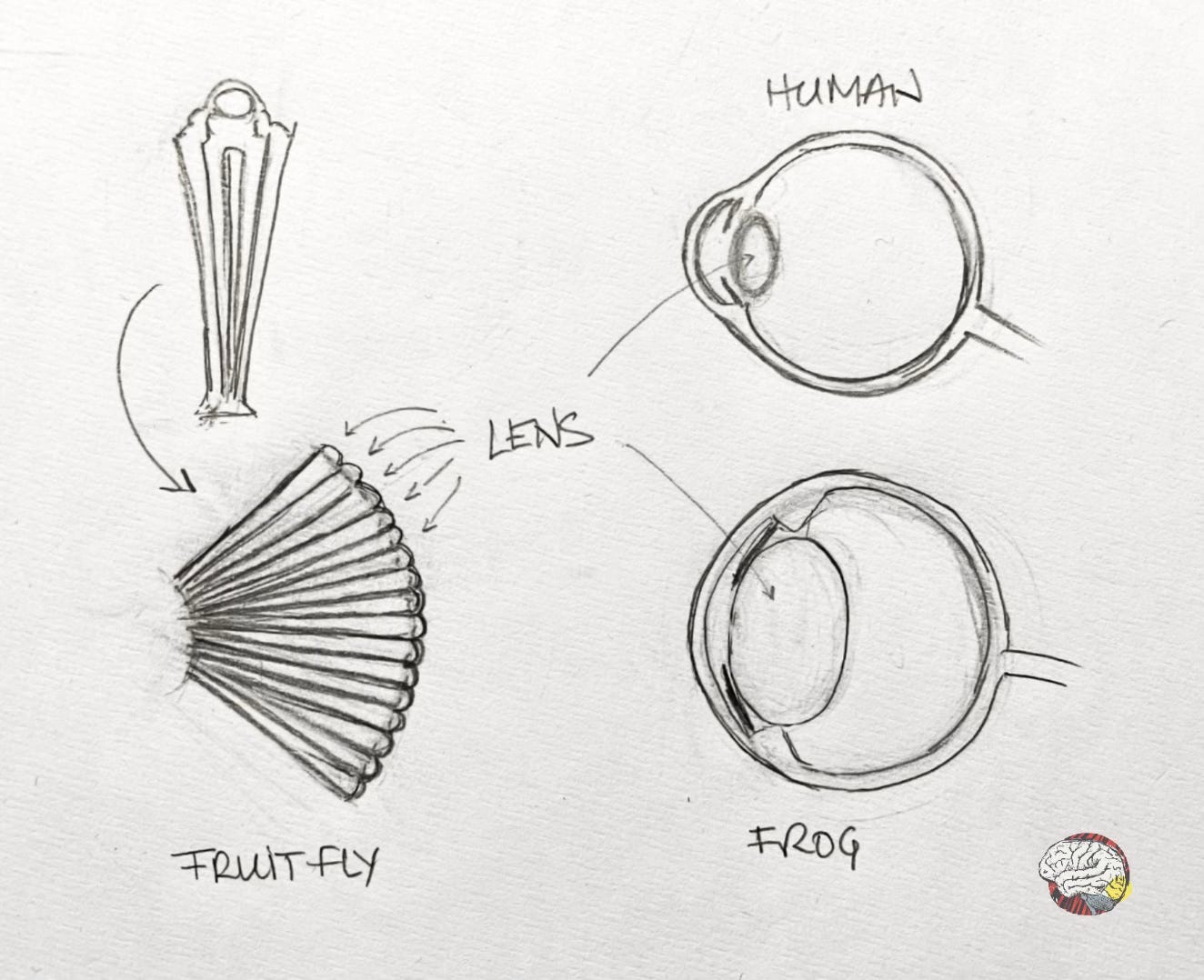

The neo-Darwinist view, argued by figures like Ernst Mayr (Salvini-Plawen & Mayr, 1977), was that eyes evolved independently, some secondary sources citing between 40 and 60 times. When organisms which are not related evolve similar traits independently, this is called convergent evolution. For example, both octopodes (yes, octopuses) and humans have developed camera-type eyes with a lens that focuses the image onto one spot in the retina. However, even though the design is similar, the tissue that forms the eye in the embryo comes from different cells: in the octopus, it comes from the same tissue that forms skin, while in the human, it comes from tissue that forms the brain.

How different are animal eyes?

To understand why scientists believed eyes must have evolved many times, it helps to look at just how different eyes appear across the animal world.

a) Different architectures.

There are many designs beyond camera eyes. For example:

insects have compound eyes made of hundreds of tiny lenses,

scallops see using mirrors made of crystals that reflect light onto the retina, and

jellyfish have simple light-sensing spots and no image-forming vision.

b) Different photoreceptors, opsins and supporting molecules

Animals use different opsins (light-sensitive proteins), and crystallins (proteins that form the lens), and different supporting molecules.

c) Different developmental origins

Retinas in the eye can form from different tissues. For example, most invertebrate eyes (insects, crustaceans, many molluscs, cnidarians) derive from epidermis (skin-forming tissue), while vertebrates’ retinas are formed from neural tissue, literally as an outgrowth of the brain.

This rich diversity of eyes suggests that evolution independently stumbled upon different ways of solving the problem of detecting light, producing entirely different eye infrastructure across different animal groups. This view of multiple origins is called the polyphyletic origin of eyes.

Now, if all these eyes evolved separately, should we expect to find any patterns between them?

The case of the missing eyes

In 1915, Mildred Hoge noticed that some fruit flies (Drosophila) were born with no eyes. She recognised this was a congenital defect, but genes were not cloned at the time. She called this disorder eyeless.

Decades later, a similar condition was noticed in mice. A single defective gene called Pax6 would cause a mouse to have very small eyes, and if the mouse inherited this gene in both chromosomes, it would die before birth, lacking eyes, nose and parts of the forebrain (Hill et al., 1991). This defect was named small eye. This mouse discovery was relevant because it could help us understand a similar condition in humans, called aniridia: a genetic condition that causes people with a defective gene to be born with very small irises or no irises at all. Inheriting both defective genes is rare, but when it happens, the embryos fail to develop eyes, a nose and have severe brain damage, and consequently die before birth.

A mouse, a fly and a human walk into a lab…

In the 1990s, scientists isolated the genes behind the small eye in the mouse (Walther & Gruss, 1991) and aniridia in humans (Ton et al., 1991). It turned out they were both versions of the same gene, Pax6. So, we know Pax6 is necessary for eye formation in mammals because when it is missing, eyes do not form. But does it exist outside mammals?

Shortly after, in Walter Gehring’s lab in Basel, Quiring and colleagues (1994) sequenced the fly gene they called ey (for eyeless), responsible for the eyeless fruit fly, and found that it was homologous to the mammal Pax6. Homologous means derived from a common ancestral gene, suggesting a common ancient origin for producing eyes across mice, humans and flies.

Can these genes be “turning on” eye formation?

“The fact that small eye, aniridia, and eyeless are mutations in homologous genes suggested to me that Pax6 might be a master control gene specifying eye development in both vertebrates and insects.” Ghering, 2005

Now, in scientific terms, this is still not enough. Correlation does not… You know how it goes.

All we know this far is that when the Pax6 gene is not working, eyes fail to develop, and that this is true across different phyla (insect and mammal). However, this only suggests that Pax6 is necessary for eyes to develop. This does not necessarily mean that it is the switch that triggers eye formation.

How can we test this? Have a think before you read on.

The gain-of-function experiment

Can the Pax6 fly equivalent gene ey create eyes where they are not supposed to be?

Fly → Fly

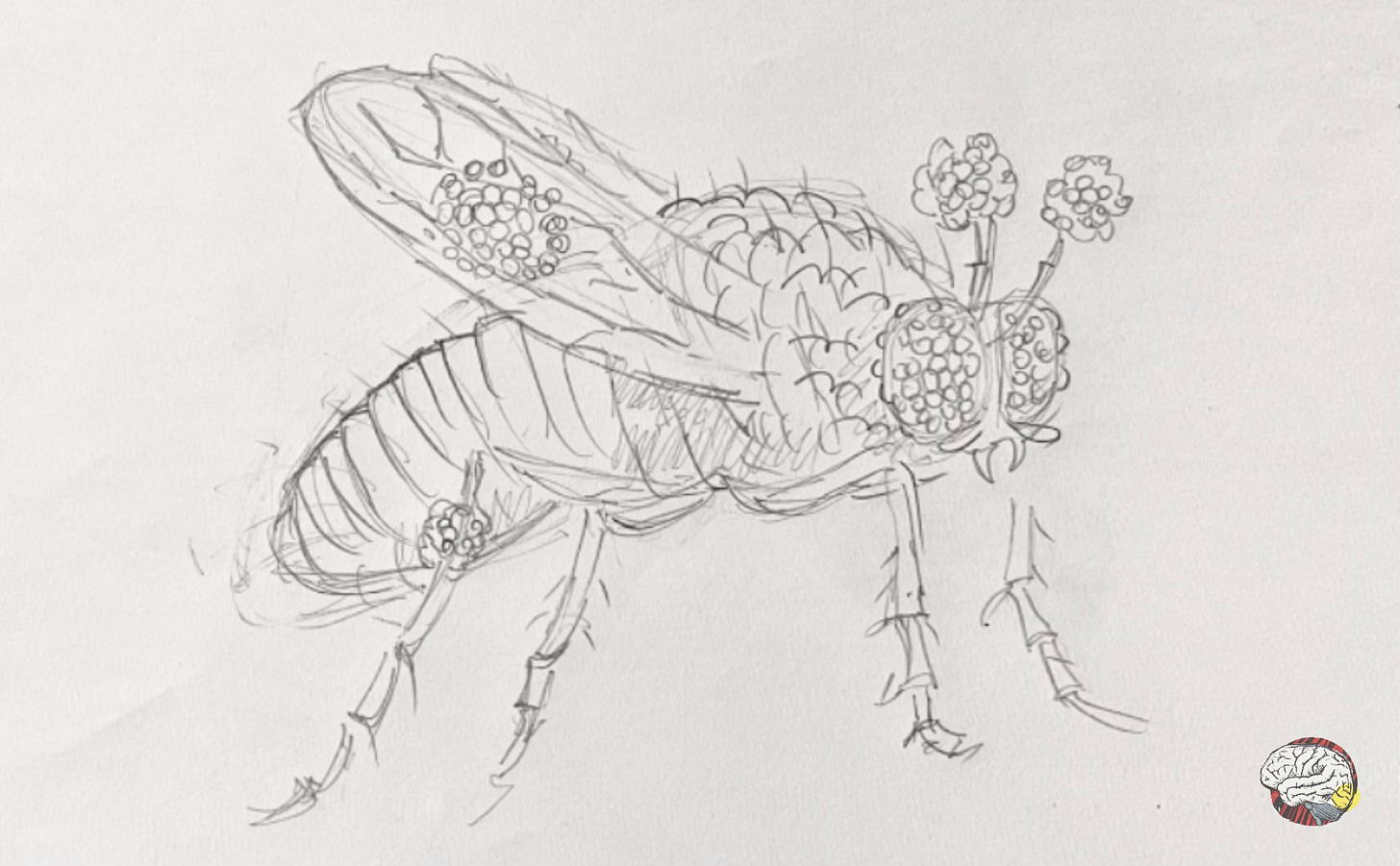

Halder, Callaerts & Gehring (1995) performed a groundbreaking experiment. They induced the ey gene (homolog to Pax6) into a different section of their genome that codes for appendages. The result? The flies grew fully formed eyes— on legs, on wings, even on the antennae. These are called ectopic eyes because they appeared outside of their usual location.

What have we learnt? This Pax6-homologue gene -by itself- seems to be enough to trigger the entire cascade of events for eye formation. So Pax6 is not only necessary, but on its own, it is sufficient to initiate eye development, acting as a master switch that says “build eyes here”.

But if this gene is present in different species, we should be able to transfer this gene across species, right?

Mouse → Fly

Fly and mouse eyes are very different: the fly’s compound eyes are mosaics made of hundreds of tiny lenses, while the mouse has a camera-type eye with a single lens focusing light onto a retina, like human eyes.

To get a closer definition of the function of Pax6, the next step was to introduce foreign Pax6, this time from a mouse, into the fly. The result will shock you! (I am sorry, I could not help myself.) But it is crazy: not only did the fly developed ectopic eyes, not only were they also fully formed and functional, but they were compound fly eyes, built under the instructions of the mouse gene.

This confirmed that Pax6 triggers the process, acting as a master switch, but the genetic recipe for making the new eyes comes from the host.

Fly → Frog

In the late 1990s, Callaerts and colleagues (1997) and Chow and colleagues (1999) attempted to produce ectopic eyes on frogs using the eyeless fly gene (homolog to Pax6). The result was patches of retinal tissue and lens structures, but no fully functioning eyes. Many reasons can be at play: the gene can activate the pathway, but to develop a full working eye, it needs the correct signals from local surrounding tissue to tell it how and when to develop the eye (Callaerts). It is also possible that the regulatory genes that act downstream of Pax6 may not be compatible in the frog. so the cascade cannot run to completion (Chow).

Pax6 in earlier animals: how far back can we trace this gene?

Pax6 has been found in an astonishing range of animals, from simple worms to vertebrates. It is so fundamental to early nervous-system patterning that even animals that have lost their eyes over evolution still retain this gene. For example, C. elegans is a nematode (a worm) that has no photoreceptors at all, yet it has conserved its Pax6 homologue. Remarkably, this gene from C. elegans can still induce new eyes when introduced into flies.

This suggests that Pax6 could have existed before eyes evolved, where it likely helped regulate the development of early neural structures, and was later “recruited” into also controlling eye formation when photoreceptive organs began to appear.

One eye to see them all

This evidence points to a single origin and is consistent with Darwin’s proposal of a simple ancestral photoreceptive system: a proto-eye.

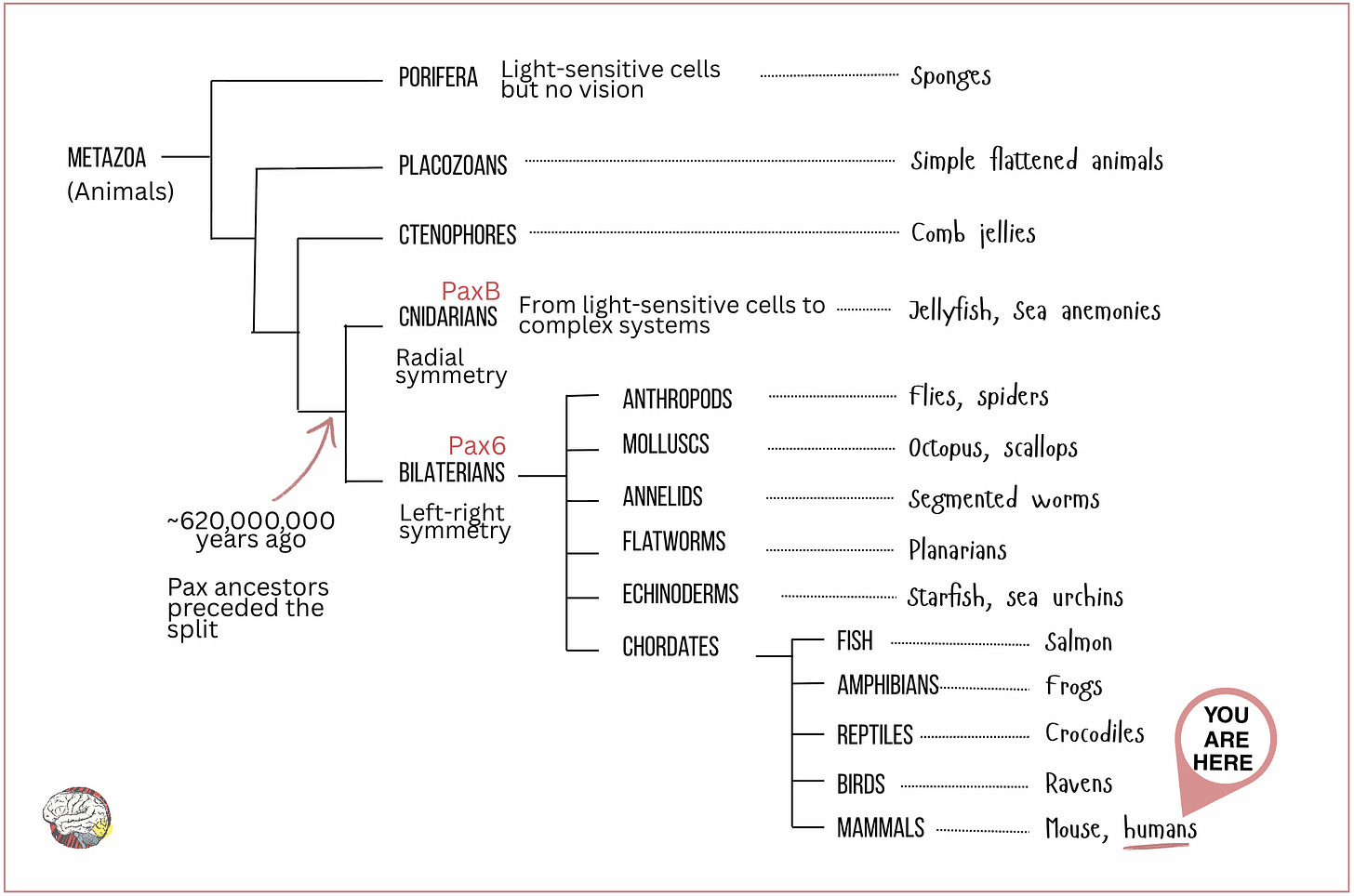

The theory of a single origin for all eyes, called monophyletic theory, argues that a core group of regulatory genes, with Pax6 (or its ancestral paralogue PaxB) at the top, was conserved throughout evolution and repeatedly used to build eyes in different animal groups (Gehring & Ikeo, 1999).

The fact that the Pax family of genes are present in such a wide range of species indicates that this regulatory toolkit must have existed in a common ancestor that lived before the cnidarian-bilaterian split, about 620 million years ago. Quite the survival record. That places Pax6 just before the Cambrian explosion, the burst of evolutionary innovation that produced most major animal body plans. See the phylogenetic tree below.

- Bilaterians include all animals with a symmetrical organisation, i.e. with a front-back and left-right axis, such as flies, humans, frogs, spiders and scallops.

- Cnidarians, in contrast, are radially symmetrical: jellyfish, corals, sea anemones and others.

Intercalary evolution: from one eye to many eyes

A proto-eye would have been regulated by an ancestral Pax6-like gene which would initiate eye formation. Further downstream, additional genes would provide more specific instructions for all the stages involved in building the eye. Over evolutionary time, new genes were added, modified or removed. Intercalary evolution suggests that while the regulatory genes at the top remain the same, different steps were inserted in between the older ones, resulting in eyes with increasing developmental complexity without altering the ancient core.

There are two main mechanisms for new genes to enter the pathway:

Gene duplication:

A gene is accidentally duplicated, and the spare copy is free to specialise into a new function. For example, some insects have only a single Pax6 gene, but in flies its Pax-like gene duplicated, resulting in 2 regulatory genes: ey and toy (twin of ey), which now form a two-step regulatory loop but still sits at the top of the pathway.

Enhancer fusion (gene recruitment):

A gene that was not involved in vision is “recruited” into a new function. An example of this is a gene called drosocrystallin, which made the protein used to build the insect’s exoskeleton. This gene was recruited, and part of the protein it made became the lens in the eye, contributing to its transparency and refractive function. The name is confusing, but an “enhancer” is simply a short DNA sequence that initiates a process.

Over millions of such iterations, these additions accumulated in different lineages and formed all the designs that exist today. This also explains how eyes can be so wildly different in structure, optics and development, while still conserving the same regulatory gene.

Choose-your-own-adventure — but for genes

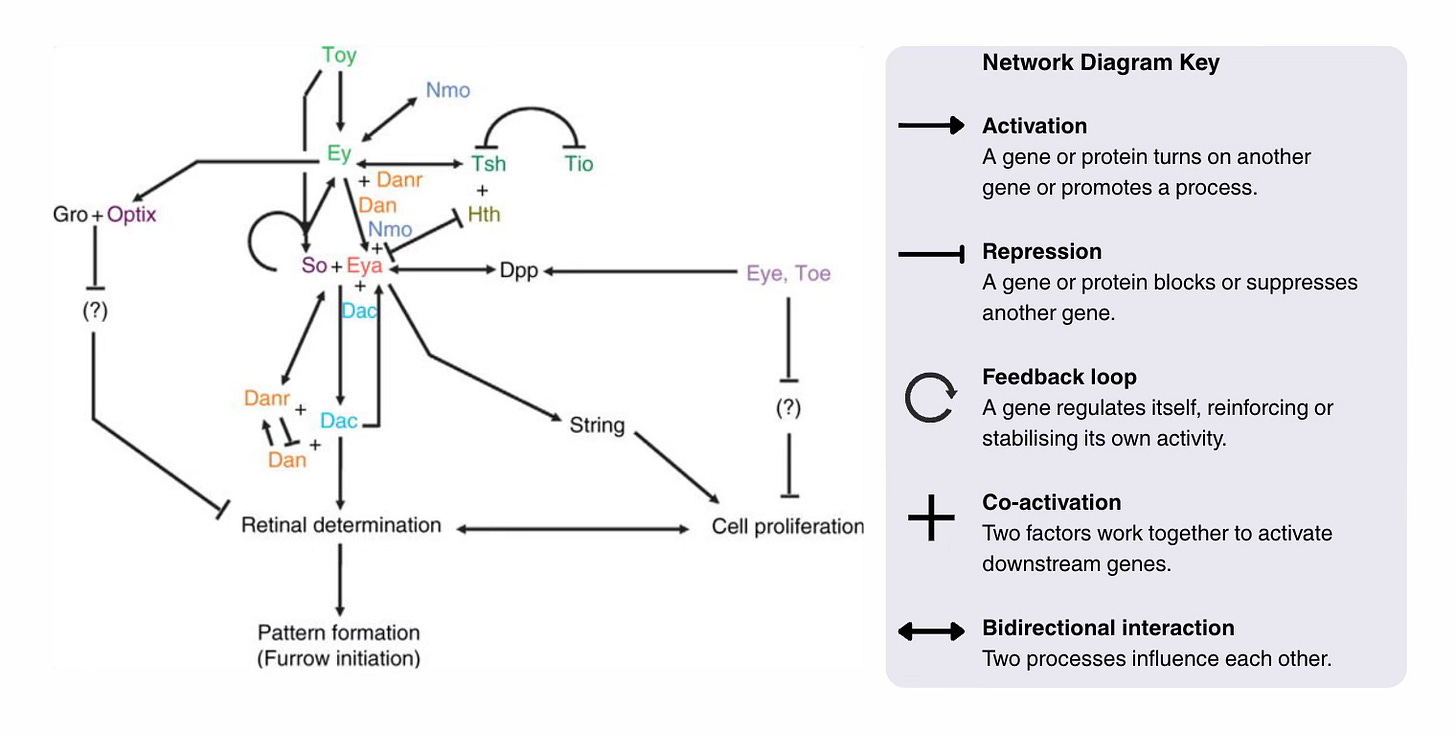

It is easy to imagine this as a linear process with Pax6 at the top of a neat top-down chain, but in reality, it is more of a network where each gene’s activity depends on the combined input of several others. This distinction matters because it explains how the same genetic toolkit can “order” such radically different eyes.

Pax6 does not act alone.

At the core of this network is the set of genes known as the Retinal Determination Gene Network (Kumar, 2009a,2009b). For simplicity, I will talk about the fruit fly but homologues of these genes exist in most bilaterians. See the network diagram,

In the fly, the regulatory network is made up of the eye determination genes: ey and toy (the Pax6 homologues), So, Eya, Dach, and Atonal. All of these genes regulate one another, for example, via feedback loops, dampening or activating each other, allowing fine control over the process. There is no single switch but rather a flexible regulating system that provides both stability and flexibility to the eye design.

A second regulatory layer comes from external signalling pathways (Hth, Dpp, and EGF), which feed into the network at multiple points. These genes provide timing and positioning cues to ensure that at the local level, the different processes that build the eye happen in the right order and in the right place; they provide the context.

The same regulatory genes can be reused or rewired to produce new forms. Evolution often works with old parts in new ways.

Once we see that eye development relies on an interconnected network where all genes are “listening to many voices”, it becomes clear that evolution does not need to reinvent a new system to create a novel eye. Simply tweaking a single interaction, weakening a connection, or introducing a new gene (by duplication or enhancer fusion), or even bypassing a gene entirely, will produce new eye type.

This flexibility explains why eyes can differ so dramatically across animals while still sharing a conserved set of regulatory genes, and why having the same genes does not guarantee identical organs. For example, even within cnidarians, the range of complexity of eyes is astonishing: the box jellyfish has 4 clusters of eyes, each cluster containing 3 different types of eyes, allowing it to extract different kinds of information from their environment. In contrast, sea anemones (also cnidarians) have no image-forming vision at all but have light-sensing organs to orient themselves.

Bringing it together

For a long time, it was thought that eyes had been invented multiple times independently. But the molecular evidence now points to a single point of origin.

Eyes were likely not invented from scratch over and over. They happened once. A cell became light-sensitive, probably through a random change in a protein that reacted to light.

Now comes the kicker…

Conclusion: Why does any of this matter?

Because it forces us to confront how improbable vision really is.

We trust our eyes more than any other sense, and we are right to do so: vision gives us the richest, most reliable grasp of the world, with roughly half of our brain involved in processing vision. Our eyes make it possible to understand others (humans and animals), to recognise emotions, and even to read these very words. It even allows us to understand things that we cannot actually see: science would not exist without the ability to lock in and pass on knowledge in written form.

Let this be your takeaway, if nothing else: this entire system that allows us to see beautiful landscapes, be moved by art, and look into someone’s eyes… All of this… almost did not happen. We owe this to a random mutation in a tiny cluster of cells over 600 million years ago, a genetic accident, that snowballed into everything we now experience as our visual world.

Are we not lucky?

It takes a lot of work and time to write these articles. If you find value in what you just read and want to support my work, you can buy me a coffee.

In any case, if you got this far, please like and restack, and feel free to drop any questions in the comments.

Coming next…

Now, if you want to know how eyes came about, stay tuned for the next edition, where we talk about how and why the first ever eye appeared. Spoiler alert: for millions of years, eyes were blind.

REFERENCES:

Callaerts, P., Halder, G., & Gehring, W. J. (1997). PAX-6 in development and evolution. Annual review of neuroscience, 20(1), 483-532.

Chow, R. L., Altmann, C. R., Lang, R. A., & Hemmati-Brivanlou, A. (1999). Pax6 induces ectopic eyes in a vertebrate. Development, 126(19), 4213-4222.

Gehring, W. J. (2005). New perspectives on eye development and the evolution of eyes and photoreceptors. Journal of Heredity, 96(3), 171-184.

Gehring, W. J., & Ikeo, K. (1999). Pax 6: mastering eye morphogenesis and eye evolution. Trends in genetics, 15(9), 371-377.

Halder, G., Callaerts, P., & Gehring, W. J. (1995). Induction of ectopic eyes by targeted expression of the eyeless gene in Drosophila. Science, 267(5205), 1788-1792.

Hill, R. E., Favor, J., Hogan, B. L., Ton, C. C., Saunders, G. F., Hanson, I. M., ... & Heyningen, V. V. (1991). Mouse small eye results from mutations in a paired-like homeobox-containing gene. Nature, 354(6354), 522-525.

Hoge, M. A. (1915). Another gene in the fourth chromosome of Drosophila. The American Naturalist, 49(577), 47-49.

Kumar, J. P. (2009). The molecular circuitry governing retinal determination. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1789(4), 306-314.

Kumar, J. P. (2009). The sine oculis homeobox (SIX) family of transcription factors as regulators of development and disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 66(4), 565.

Kumar, J. P. (2010). Retinal determination: the beginning of eye development. Current topics in developmental biology, 93, 1-28.

Quiring, R., Walldorf, U., Kloter, U., & Gehring, W. J. (1994). Homology of the eyeless gene of Drosophila to the Small eye gene in mice and Aniridia in humans. Science, 265(5173), 785-789.

Samadi, L., Schmid, A., & Eriksson, B. J. (2015). Differential expression of retinal determination genes in the principal and secondary eyes of Cupiennius salei Keyserling (1877). EvoDevo, 6(1), 16.

Salvini-Plawen, L. v., & Mayr, E. (1977). On the evolution of photoreceptors and eyes. In M. K. Hecht, W. C. Steere, & B. Wallace (Eds.), Evolutionary biology (Vol. 10, pp. 207–263). Plenum Press.

Ton, C. C., Hirvonen, H., Miwa, H., Weil, M. M., Monaghan, P., Jordan, T., ... & Saunders, G. F. (1991). Positional cloning and characterization of a paired box-and homeobox-containing gene from the aniridia region. Cell, 67(6), 1059-1074.

Walther, C., & Gruss, P. (1991). Pax-6, a murine paired box gene, is expressed in the developing CNS. Development, 113(4), 1435-1449.

This was a fascinating article and I loved how you broke everything down so clearly. Thanks for sharing.

This was so out of my lane, but I could not stop reading it. Yes we are very lucky, and I loved the Choose Your Own Adventure comparison, I read a ton of those as a kid!