Before Eyes, Life Was Already Sensing Light

A Hypothesis About How Life Learnt to See

Long before animals had eyes, before retinas or neurons even existed, life was already responding to light. We know that the capacity for light sensing is billions of years old, yet animal vision appeared only about 600 million years ago. So how did that ancient light-sensing capacity find its way into animals and become the basis of vision as we know it?

What follows is one way this might have happened.

In Part 1, we spoke about multicellular animals and how light sensitivity was rapidly refined into vision through changes in structure that allowed new advantageous behaviours. But light sensing did not begin with multicellular animals. It started eons before. Not figuratively, but 2 full geological eons earlier.

Light sensing predates animals by a very long time.

Light-sensing likely arose over 3 billion years ago, with cyanobacteria in the Archean eon. Cyanobacteria are preserved in fossils called stromatolites and are among the earliest evidence of life on Earth. They also provide the first evidence we have of life responding to light. Crucially, they never went extinct, so modern cyanobacteria are direct descendants of that ancient lineage.

Different lines of evidence suggest they had light-sensing capabilities that persist, in modified form, to this day:

Molecular evidence: Genomic analyses of modern cyanobacteria showed that they possess some of the earliest and most diverse photoreceptor protein families (phytochromes, cyanobacteriochromes, microbial rhodopsins). Phylogenetic analyses place these gene families deep in evolutionary trees, indicating that they originated long before animal opsins evolved.

Evolutionary continuity: When scientists compare genomes across algae, plants, and animals, they find that many genes involved in light sensing closely resemble those found in cyanobacteria.

Functional evidence: Modern cyanobacteria show light-driven behaviours. Part 1 explains why this is important. Some of these behaviours are:

phototaxis,

circadian regulation, and

chromatic acclimation. This means adjusting which light-absorbing pigment they use to match the colour of light available at any time. It is so tempting to go down that rabbit hole, but I shan’t.

This suggests that animal photoreceptors may have been built on ancient light-sensing technology. What remains now is to explore how this machinery made it into animal DNA.

The light-sensing cell

In the traditional view, animal photoreceptors arose through gradual reuse and modification of existing cells within early animals. As multicellular organisms evolved, some cells became specialised for electrical signalling and, through small molecular changes, began responding to light.

This view does not assume any direct evolutionary link between animal vision and the light-sensing seen in cyanobacteria, which is treated as a separate, much older phenomenon.

This is about to get fun.

According to one hypothesis, photoreception did not arise only by differentiating an ancestral animal cell type. Instead, it may have been acquired through several layers of endosymbiosis, basically: one organism living inside another. This is why Walter Gehring (2005) calls it the Russian Doll model.

Let us talk endosymbiosis. This refers to an organism engulfing another, but instead of digesting it, they coexist and both benefit from the merger. It is a widely accepted evolutionary mechanism. It is how we think mitochondria entered our cells and became the powerhouse that fuels you. The mitochondrion has its own DNA, which is different from the DNA of the cell that contains it. But I digress.

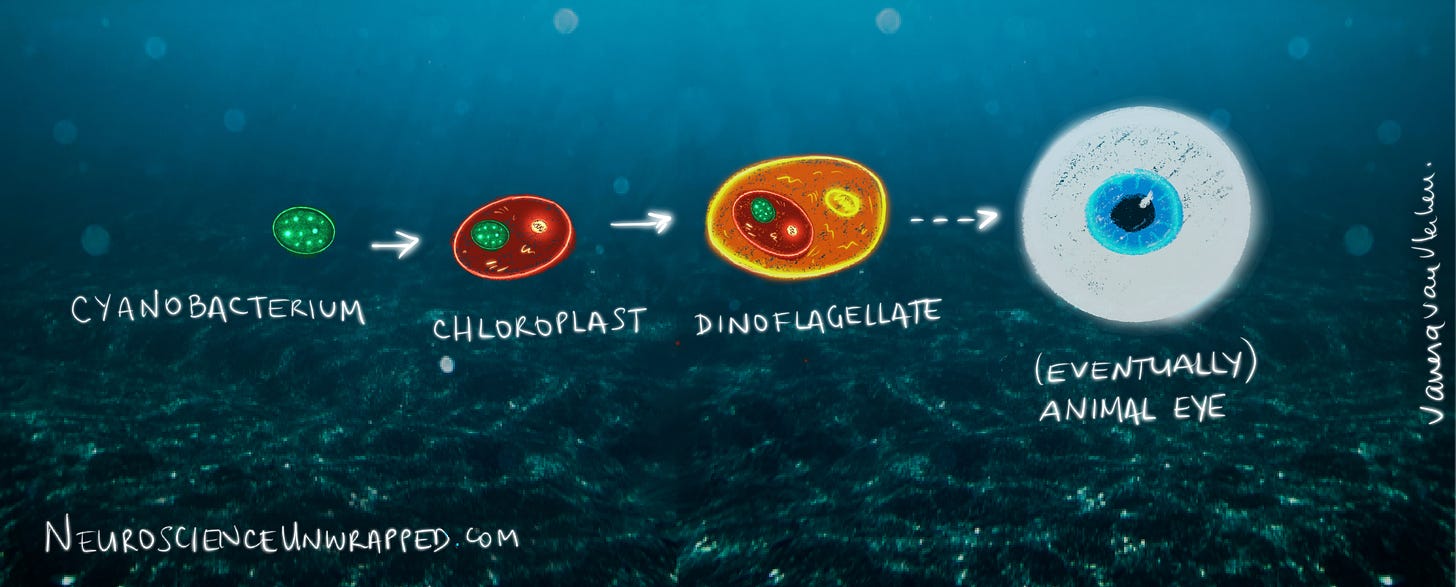

Here is Gehring’s symbiont hypothesis, step by step.

Step 1: A light-sensitive bacterium

It starts with cyanobacteria. They are a single cell without a nucleus. They can harness light because they contain photopigments, molecules that undergo a reversible chemical change when they absorb photons, allowing cells to notice and respond to light.

Step 2: Engulfed by red algae

At some point, a cyanobacterium was engulfed by a red alga. But instead of being digested, it lent its photosynthetic ability to the alga, making it a chloroplast. This tiny solar panel absorbs light and turns it into energy, more specifically, into food. Have you heard of eating with your eyes?

Step 3: Engulfed again by dinoflagellates

Later still, chloroplasts are engulfed by dinoflagellates, which are single cell plankton, common in marine environments. In some dinoflagellate lineages, the inherited chloroplasts were no longer used primarily for photosynthesis. Instead, they were transformed into elaborate light-sensing organelles.

One species of dinoflagellate, called Warnovia, has an ocelloid, a precursor of an eye (Greuet, 1969). This is not part of our lineage, but this ocelloid has structures that resemble a cornea, a lens, a retina complete with a membrane, and a prominent cup. But the Warnovia is still a single-cell organism. No nervous system. No multicellularity.

Let me say that again. This is, actually, a SINGLE CELL THAT CONTAINS AN EYE.

How cool is that?!

I need a minute to compose myself.

Step 4: Sharing the love – I mean, the DNA

From dinoflagellates onwards, things become more uncertain. Some dinoflagellates live inside other organisms, such as corals and sea anemones. Gehring suggests the possibility that photoreceptor-related genes could have been transferred from the DNA of dinoflagellates into the DNA of animals.

This process is known as horizontal gene transfer, meaning genes pass between symbiont and host, rather than being passed on from parent to offspring. While horizontal transfer itself is a well-established evolutionary mechanism, what remains speculative is whether photoreceptor-related genes made this jump into early animals in a way that contributed to the origin of animal eyes.

In short

The early “Russian dolls” (cyanobacterium → red algae → dinoflagellates) are supported by mainstream endosymbiosis and modern evidence of ocelloids. The idea that this process contributed directly to the origin of animal eyes remains an intriguing possibility rather than an established fact. Scientists are still looking.

Conclusion

Long before animals had eyes, light was already shaping life in single cells. By the time animals appeared, light sensing was a well-developed technology involved in metabolism and survival.

The Russian Doll hypothesis offers one possible bridge between the two worlds. It suggests that ancient light-sensing systems may have entered animal lineages through merger, not mutation alone. If this hypothesis is correct, it would mean that the origin of animal vision may not be located in animals at all, but in much older single-celled life.

Parts of this story are well supported; the final step remains speculative. But this is what gives me chills: the technology we use to see the world is billions of years old, and for the majority of this time, it was not involved in image forming at all! If the hypothesis is right, vision did not start as vision: it began as a way of producing food for the cell, was gradually repurposed for metabolic regulation, then for guiding behaviour, and only much later, refined into what we understand as high-definition vision.

Even if the hypothesis is not correct, vision is still at least about 620 million years old, only without the “producing food” step from the list above. Not any less impressive.

But what is certain is that vision is only a late chapter in a much older story. Long before sight guided behaviour, it fed life itself.

It takes a lot of work and time to write these articles. If you find value in what you just read, there are many ways to support my work. You can:

Like and restack

Start a conversation: comment, ask questions

all of the above

REFERENCES:

Gehring, W. J. (2005). New perspectives on eye development and the evolution of eyes and photoreceptors. Journal of Heredity, 96(3), 171-184.

Gehring, W. J. (2014). The evolution of vision. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology, 3(1), 1-40.

Greuet, C., & Ferru, G. (1969). Etude morphologique et ultrastructurale du trophonte d'Erythropsis pavillardi Kofoid et Swezy. Protistologica, 5(4), 481-503.

Great read!