Why Stars Disappear When You Look at Them. The Biology of Vision

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

Have you ever noticed that a star in the night sky is easier to see when you are not looking directly at it, and it seems to vanish when you do?

How is the sharpest part of our vision so bad at seeing… well, sharply?

As a child, I often stayed at my grandmother's house. At night, as I lay in bed in the dark, I could make out a small statue on a shelf, always on the edge of my vision. But every time I looked directly at it, it would vanish. Every single time. I was not the magical thinking type, even then, but not understanding why bothered me.

Now I know the mechanism behind this, and it is one of my favourite evolutionary adaptations in neuroscience.

"The visual system has deceptively simple solutions

to serve very complex visual functions"

The illusion of effortless vision

We trust that we open our eyes and reality simply filters in. The whole scene presents itself instantly and fully formed, sharp and in rich detail. We can see both in bright daylight and in near darkness. And we can also see very fast, enabling us to avoid collisions and see movement.

Yet vision is not so effortless. There are simultaneous, complementary systems at play that, combined, give us a seamless experience of sight and the illusion of a complete scene in focus. In truth, our eyes can only see sharp detail in a tiny fraction of the visual field at any given moment. The rest is computational magic.

The brain is very expensive, and light-sensitive cells are particularly energy hungry. We need to detect different features in all light conditions, very fast, but also as economically as possible... Enter the cones and rods.

Introducing the cones and rods

We manage fast, sharp vision by relying on the two main photoreceptor types: cones and rods, each with different specialisations. Both respond to light by converting photons (the smallest unit of light) into electrical impulses. In evolutionary terms, the cones evolved from rods, so the underlying mechanisms are the same, even though their functions are almost opposite (more on functions later).

Remarkably, it is how they are wired into the visual pathway and their distribution across the retina that determines how much detail and light we can detect. This setup provides a flexible system, capable of high detail, fast response and impressive sensitivity in near-total darkness – and that is what gives us this wonderfully rich visual experience.

Same but different

I said earlier that cones evolved from rods, yet they have almost the opposite function. There is a bonus table at the end of the article comparing them side by side, so you can just enjoy the reading for now.

What they have in common: they convert light to electrical signals.

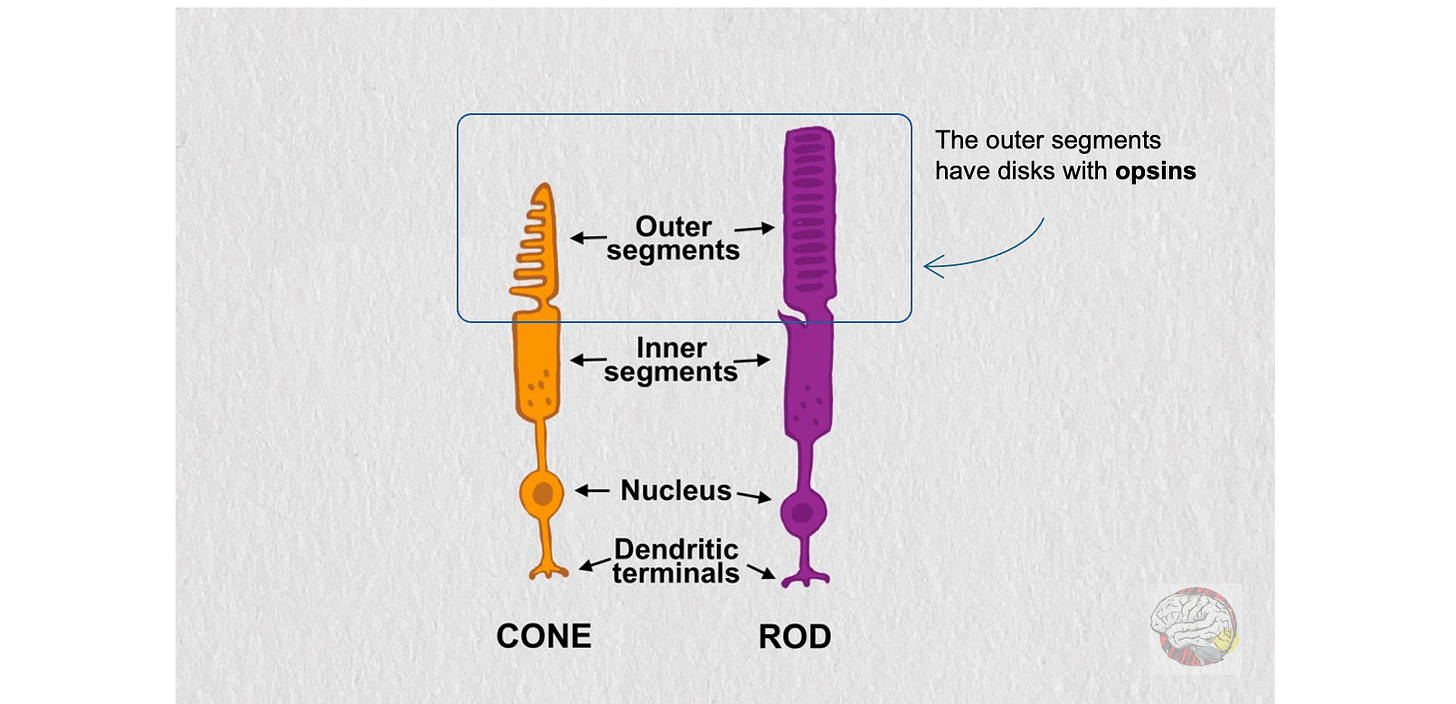

Light enters the eye and is absorbed by opsin proteins inside hundreds of stacked disks in the outer segments of the photoreceptors. When activated, these proteins change shape and shut ion channels in the membrane, altering the cell’s electrical charge. This triggers a cascade of events that generate an electrical impulse, which is the currency of neurons.

This process is called phototransduction because it transforms (“transduces”) light into electrical impulses.

What sets them apart: their opsins

Cones and rods have different opsins: rhodopsin in rods and cone opsins in cones; they have different sensitivities.

The opsins in cones: masters of speed.

Cone opsins respond to light very fast and can shut off the photoreceptor membrane in 3-5 milliseconds. The entire process, from photon to electrical impulse, can happen in 9 to 18ms. Not only that, but cones can recover fast and be ready to fire again in just 3ms (compared to hundreds of milliseconds in rods) (Lamb, 2022). This allows us to see fast changes in light, and therefore, we can see smooth movement. Our cones can detect flickering light at a frequency of 100 times per second or 100 Hz (Tyler & Hamer, 1990), which is why motion appears fluid rather than jumpy or stuttered.

As a side note, cone opsins are responsible for our ability to see colour. Each cone contains one of three opsins, each tuned to a particular wavelength of light. These three types together form the basis for colour vision. This is very eloquently explained here (scroll to “How we see colour”).

The opsins in rods: masters of amplification.

Unlike cones, which require a bright light (many photons) to respond, rods only need a single photon to fire a spike. This is because a single rhodopsin molecule initiates a cascade of internal reactions that amplifies the signal dramatically at every stage (Baylor et al., 1979; Lamb, 2016). This amplification allows us to make the most of very little light.

Here is the downside: rods have a very slow recovery time until they can fire again. We notice this when walking from a bright area into a dark room, it takes time before we can see clearly again. Research has timed this at a maximum of 40 minutes for optimal vision after an intense light exposure (Lamb & Pugh, 2004).

The deceptively simple solution: Conversion

This is my favourite concept in neuroscience because it illustrates how delightfully simple mechanisms can serve very complex features.

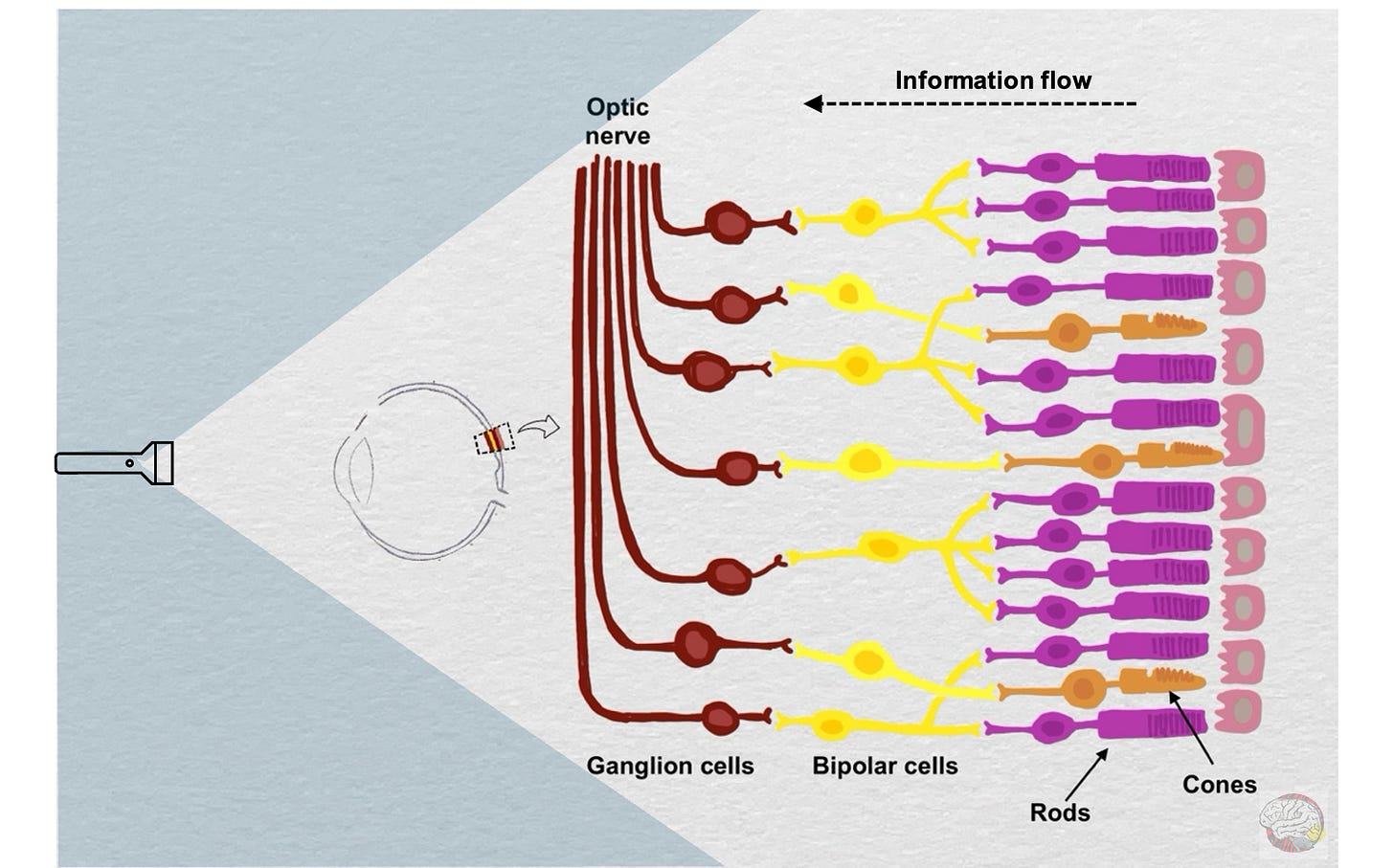

In the image (below), light comes from the left and is picked up by the cones and rods at the back of the retina. That might feel counterintuitive, but retinal cells are transparent, allowing light to pass through.

Photoreceptors respond to light by generating small electrical signals (graded potentials). These signals are passed on to bipolar cells, which then relay them to ganglion cells. The axons of the ganglion cells bundle together to form the optic nerve, which carries visual signals to the visual cortex via the thalamus. This setup means that the signals are integrated and modulated at every stage, even before they leave the retina.

Crucially, the way the cones and rods connect to ganglion cells is different, and this is the core engineering principle that gives us both high sensitivity and high resolution with a simple design.

Many rods converge onto a single ganglion cell.

Conversion gives the ganglion cell a very high light sensitivity. It gives it a broad receptive field – a wide map of photoreceptors that increases the chances of catching any light. If any of the photoreceptors is hit by a photon, the ganglion cell knows about it. The trade-off is that it cannot know where (which rod) the light is coming from. So, we say that the spatial specificity is very low, resulting in a blurry image.

But this is not all, there is also a summation effect. Think of the sound of a single person gasping versus that of a crowd gasping. Pulling together signals from many photoreceptors results in a stronger signal. This is why rod vision gives us high sensitivity to light, allowing us to see in very dim conditions but at the cost of a rather low resolution.

By contrast, each cone relays information to its own ganglion cell.

This means that this ganglion cell knows exactly where the light is coming from, resulting in excellent spatial resolution and a sharp image. The downside of only receiving input from a single photoreceptor is that this ganglion cell will require more light (that is, more photons hitting that single cone) to “summate” enough input together to trigger an electrical impulse. This is why cones only activate in bright environments while rods take over in low lighting.

“Our eyes prioritise detail where it matters most

and save energy everywhere else.”

Location, location, location

Vision is not equally sharp across the retina. This is because we do not need detailed information from every part of our visual field at once. The brain is highly energy hungry, and photoreceptors are some of the most metabolically expensive cells in the body. It is therefore most useful to detect fine detail only when and where we need it and conserve energy.

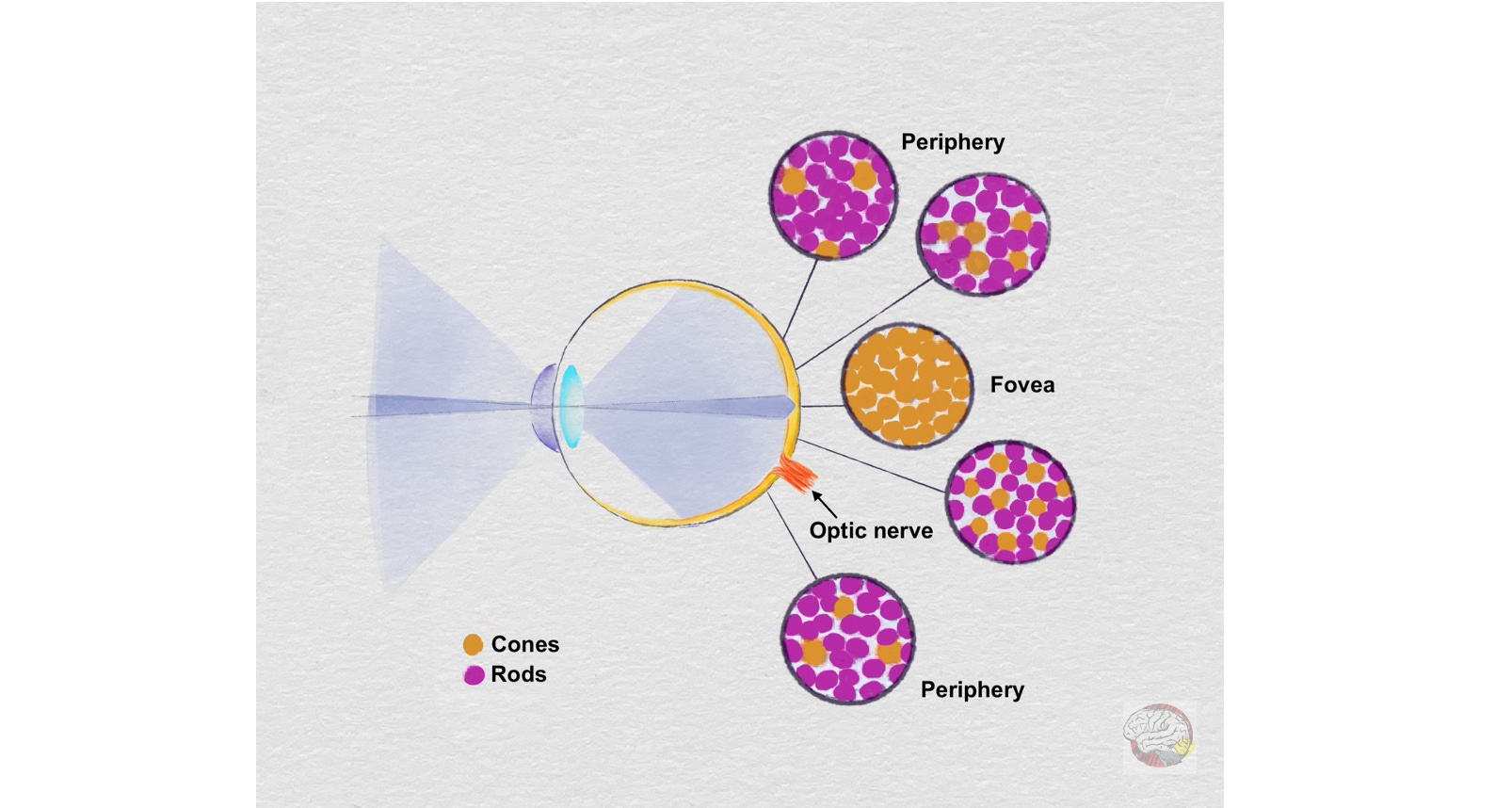

The light that enters the eye is bent primarily by the cornea and further adjusted by the lens to converge on a central area called the fovea. This region contains only cones (Curcio et al., 1990) and is therefore specialised to detect fine detail. It is what allows us to read interesting articles like this one, or to see the excitement on someone’s expression as you tell them about cones and rods.

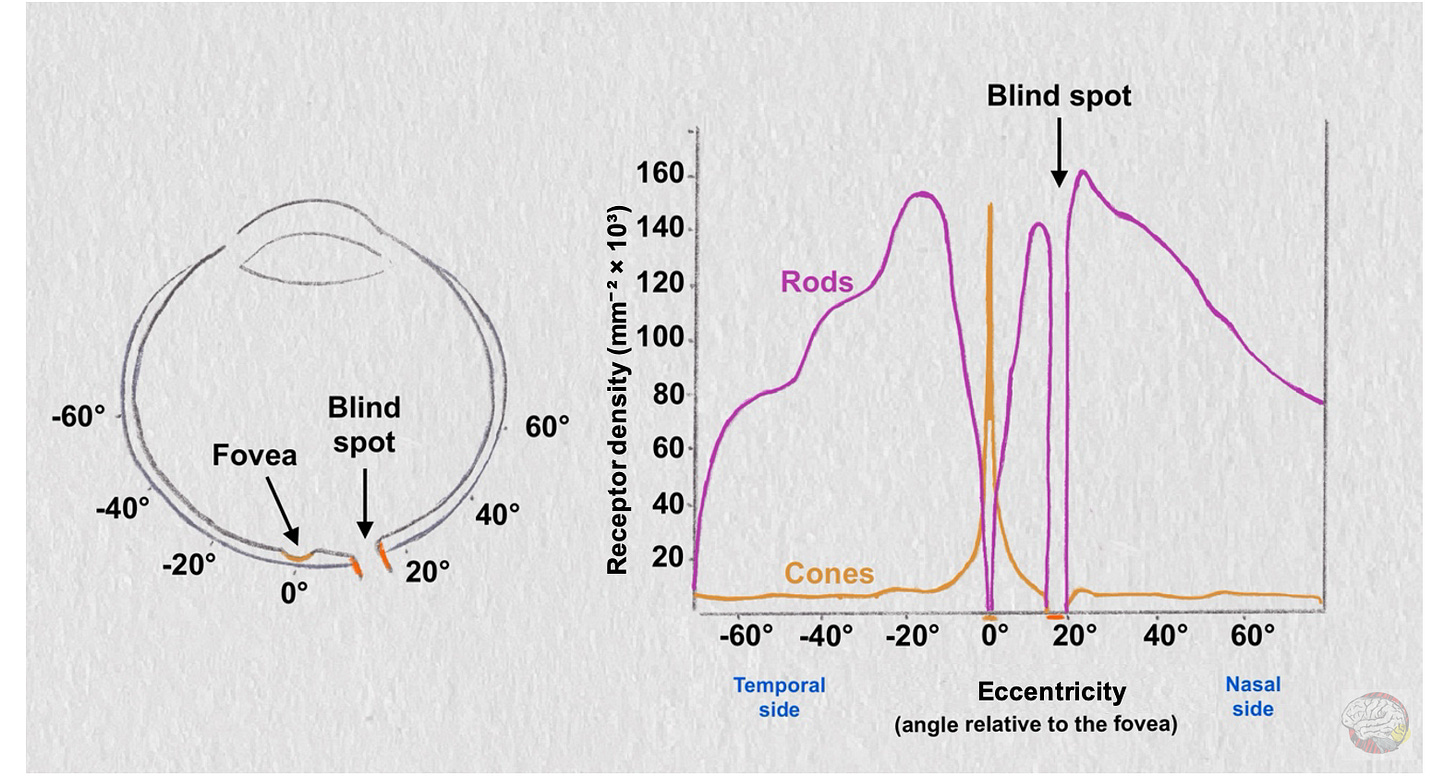

However, cone density drops sharply just outside the fovea and, even though there are still cones in the periphery, this area is dominated by rods (see chart below).

This is because we do not need high detail in the periphery of our vision; a few cones are enough. What is crucial for survival is to detect fast changes in light in the corner of our eye: we just need to sense that something is coming at us. If it turns out to be a car or a tiger (I do not know where you take your walks), it is less urgent. A built-in bias to flinch when something comes at us gives us enough time to look at it (thus making the image land on the fovea) and figure out what it is.

Rods are a different kind of hero. Rods are far more abundant than cones, in a ratio of about 20:1 (or 95% of all photoreceptors), and they are found exclusively outside the fovea. They are not specialised for sharp vision but for detecting faint light in very dim conditions. It needs to be quite dark for rods to take over, which typically happens at night. Fittingly, the time it takes for rods to recover after exposure to bright light (up to 40 minutes) can easily accommodate the time it takes for dusk to fall.

This elegant configuration combines the ability to perceive the smallest details without sacrificing the ability to react instantly to potential threats. And we have the added superpower of night vision.

It is an optimised system that balances precision with sensitivity: Foveal vision: only cones, high detail, low sensitivity. Peripheral vision: mostly rods and fewer cones, high light sensitivity, low detail (Remember that cones in the periphery still support daytime vision.)

Night vision

Our visual system operates in different modes depending on light levels:

cone-driven photopic vision in bright light,

rod-driven scotopic vision in darkness, and

combined input in mesopic vision in conditions such as dawn, dusk or streetlight.

Mesopic vision is far too complex to include here, but for now, it suffices to know that it is not either/or, but that there is an overlap when both cones and rods contribute to vision. If you are observant, you can tell when you are using mesopic vision because colours look a bit strange. Ask me about this at your own peril.

Cones require bright light to trigger an electrical impulse, so they do not get activated in the dark. Rods, in contrast, are optimised to amplify scarce light and, for this reason, in bright environments they become overwhelmed or “bleached”. So, while cones are active in bright daylight, rods take over in darkness.

Once our eyes have adjusted to near darkness (almost pitch-black), the high light sensitivity of rod vision allows us to detect shapes and movement even in starlight. However, since rod-driven vision has very poor spatial specificity, we cannot see sharp detail in the dark. Objects also appear colourless because colour is mediated by cones, which are now inactive.

This transition between rod-driven and cone-driven vision is another way our visual system optimises perception. Between the two photoreceptor types, it covers a vast range of light conditions, from 0.000001 to 100,000,000 nits. That is an impressive 14 orders of magnitude.

Now, if you are thinking our night vision is not really all that good, consider when was the last time you used your scotopic (rod-driven) vision? Think about it: to enter full superpower rod-driven mode, you must be in near pitch-black (below 0.001 nits) for up to 40 continuous minutes. That is the light level of a moonless night in the countryside.

To help you work this out, I found you some numbers: if you read in bed, you will need about 10-20 nits of light on the page. A typical phone screen emits around 300-400 nits, going up to 2,000 nits. A 55-inch television screen has a luminance of 400 nits. All of those are within the photopic (cone only) range.

You are equipped to see in the dark. Are you not tempted to test your night vision superpowers?

All of this for the illusion of effortless sight

Despite having the same core mechanism, photoreceptors have evolved complementary strengths: rods amplify light, cones deliver sharp, smooth movement and colour vision. Together, they give us the illusion of a rich and detailed vision in all lighting conditions.

All of this happens so fast; to see the world, clearly, sharply, in motion, across bright and dark environments. We rarely consider the enormous computational power and feats of biological engineering required to just open our eyes and let the world simply filter in.

Vision is the most exciting magic trick!

I bet you were having so much fun, you forgot the question that started this. Go on, have a go:

Why do stars in the night sky seem to vanish when you look straight at them? A. Because the star’s light is scattered by the lens. B. Because cones are more sensitive to dim light. C. Because the centre of your vision does not contain the very light- sensitive rods. D. Because stars are shy.

In this article, we have only looked into the retina. I have not touched on how the brain uses this information to see edges, colour, contrast, movement or biological motion and how all of this links to emotion or recognising familiarity. Or even how we manage not to get dizzy every time we move our eyes! All of this is coming in due time. Although about visual motion, you can already check out this link.

If you enjoyed this, do subscribe for more. I am always open to questions and challenges, so feel free to suggest new topics.

Bonus Content: Quick comparison of cones and rods (table below)

What you have learnt:

Duplex theory of cones and rods and their different specialisations

Conversion: light sensitivity vs spatial resolution

Spatial distribution: cones in the fovea, rods (and fewer cones) in the periphery

Visual modes: scotopic, photopic and mesopic vision

Seamless integration for a rich visual experience, capable of simultaneously having sharp perception and a fast response to danger

It takes a lot of work and time to write these articles. If you find value in what you just read and want to support my work, you can buy me a coffee.

In any case, if you got this far, please like and restack, and feel free to drop any questions in the comments.

References:

Baylor, D. A., Lamb, T. D., & Yau, K. W. (1979). Responses of retinal rods to single photons. The Journal of physiology, 288(1), 613-634. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012716

Curcio, C. A., Sloan, K. R., Kalina, R. E., & Hendrickson, A. E. (1990). Human photoreceptor topography. Journal of comparative neurology, 292(4), 497-523. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902920402

Lamb, T. D., & Pugh, E. N. (2004). Dark adaptation and the retinoid cycle of vision. Progress in retinal and eye research, 23(3), 307-380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.03.001

Lamb, T. D. (2016). Why rods and cones? Eye, 30(2), 179-185. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.236

Lamb, T. D. (2022). Photoreceptor physiology and evolution: Cellular and molecular basis of rod and cone phototransduction. The Journal of Physiology, 600(21), 4585-4601. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP282058

Osterberg, G. A. (1935). Topography of the layer of rods and cones in the human retina. Acta Ophthalmologica. Supplementum, 6, 1–103.

Tyler, C. W., & Hamer, R. D. (1990). Analysis of visual modulation sensitivity. IV. Validity of the Ferry–Porter law. Journal of the Optical Society of America A, 7(4), 743-758. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.7.000743

Wow, this was such an amazing read... I need time to digest it but I really enjoy learning how things work.

This was an absolutely fascinating read...beautifully written and thoroughly explained!

I especially appreciated how such a complex biological system was broken down into an elegant, intuitive story.

The comparison between rods and cones, and the idea that vision is engineered to balance sharpness and sensitivity, gave me a whole new appreciation for what’s happening behind the scenes every time I open my eyes.

The question at the end tied it all together so cleverly. I’ll definitely think differently now when I glance at stars in the night sky...or rather, when I don’t look directly at them!

Looking forward to more content like this.